Alaska barley bread.

Alaskan sourdoughs

09/18/2019

A drive through Alaska can yield a number of head-scratching signs and business names — Tundra Tanning & Taxidermy and Houston Grass Station were two favorites — but none baffled me quite like the “Sourdough Pawn & Gun” sign I passed on my first full day in Alaska. After an overnight flight into my summer home, I craned my neck on the drive from Anchorage to Talkeetna to make sure my tired and bread-crazed brain hadn’t summoned a mirage. But no, it was there. And ever since, every time I pass the little shop on the side of the highway on a drive south, it brings a smile and a reminder of all the things you don’t know you don’t know.

Soon after, I learned that sourdough can be used to name a bread or a person in Alaska. It’s something most tourists and visitors learn quickly, because every port town and day trip along the cruise routes has at least one sourdough centric spot: Sourdough Sunshine B&B in Seward, The Fresh Sourdough Express in Homer, the Klondike Doughboy in Skagway, even a Sourdough Campground all the way in Tok. The word’s dual use comes from sourdough’s rich history on the frontier and in mining camps. Just like sourdough the bread’s inextricable link to San Francisco from the gold rush days, sourdoughs the Alaskans are seasoned prospectors, miners and frontiersmen who, as stories in books like Alaska Sourdough and Cooking Alaskan say, carried their sourdough starters with them past the edges of civilization, far from the reach of reliable dry yeast or a general store. They kept them close to their bodies for protection from Alaska’s bitter cold, and hauled pounds of flour with them through Chilkoot Pass to make hotcakes to fuel them through the tundra (As Alaska Sourdough tells it, there was also an unfounded fear of the effect that baking powder could have on a man’s … performance). The sourdough moniker took hold, with a ragtag summit attempt up Denali in 1910 even being called the Sourdough Expedition.

But back to sourdough the bread. In Talkeetna, the Roadhouse boasts of its sourdough pancakes, a staple in a frontiersman’s diet. The Flying Squirrel Bakery where I worked casually slides sourdough into just about every bread recipe, whether it relies on packaged yeast to leaven the loaf or not. And that seems to be the common thread all Alaskan sourdough bread shares, setting it apart from the laborious, technical loaf that San Francisco sourdough has come to equate of late. Alaskan sourdough is utilitarian and un-finicky.

My take on a classic crusty sourdough four months ago, before Alaska.

My earliest concept of sourdough was a narrow one, driven by the same stereotypical images of San Francisco’s tangy, crusty, airy white loaf. Only in the past four years of baking have I come to understand sourdough’s scientific origin as a wild yeast that can be used to leaven any sort of bread, from a hearty multigrain to a buttery brioche. And it seems that those people who use sourdough as both a yeast and a flavor are divided into two camps.

There are sourdough purists, who want to use sourdough as a bread’s sole leavening agent and of whom I should probably self-identify (I spent an embarrassing amount of time finding and perfecting a naturally-leavened challah recipe). We schedule, weigh and temperature adjust our sourdough feedings to align with optimal yeast and acid levels before even starting to mix a levain or pre-ferment, much less the dough itself. I’m on the more lax side of this technical bunch, given that I rarely mess with dough temperature or long bulk fermentation times at home. Others are in eternal pursuit of the picture-perfect crumb structure, through hours of folding and fermenting their doughs. And that approach can be intimidating, especially as a beginner or a less scientifically-minded baker.

And then there are sourdough utilitarians, who are less showy but more plentiful, as evidenced in down-home Alaskan recipes. They throw together cups of starchy potato water and handfuls of flour in a crock on top of the stove to create their starter. And their reliable secret to airy kitchen creations, so as not to waste precious ingredients on things like sourdough discards or unleavened baking failures, is to combine a separate portion of that sourdough, at any point in its yeasty life cycle, with a bit of baking soda or commercial yeast. And there’s a magic there, too. The dough expands on a hot surface, whether as hotcakes or a sandwich loaf, and is delicious and filling regardless of how its crumb structure or sour tang came out. Just about any sourdough eaten warm on a cold day tastes like a miracle.

Alaskan sourdough is the perfect example of the make-do attitude that is so prominent and admirable to me up here. “Recipes” can never truly be followed. Timelines can’t be perfectly adhered to. Sometimes, the electricity can’t even be relied on. It’s all just an outline. Back in the days of the gold craze, there was no corner store; you had one resupply a year. Today, the nearest grocery store is a 20 minute drive away from downtown Talkeetna — a vast improvement, but also worlds apart from today’s bustling metropolises — and its shipments are at the mercy of a cascade of factors that I saw all too clearly when the fire season stripped its shelves. People who live off the grid don’t even have that luxury.

So ingredients are foraged, swapped, omitted or added as needed. There’s not much corn, but there’s a lot of Alaska grown barley and plenty of spent grains. Rhubarb is impossible to avoid in the height of summer, and fiddleheads are impossible to find. The tasty spruce tips disappeared seemingly overnight during this summer’s heat. Everything has berries in it at the end of the season, but fresh salmon tapers off by September, leaving canned, smoked or dried alternatives. The cost of tahini or mangoes or some other “exotic” ingredient is prohibitive if you can find it outside of Anchorage, even though they would be considered a staple in any D.C. Safeway.

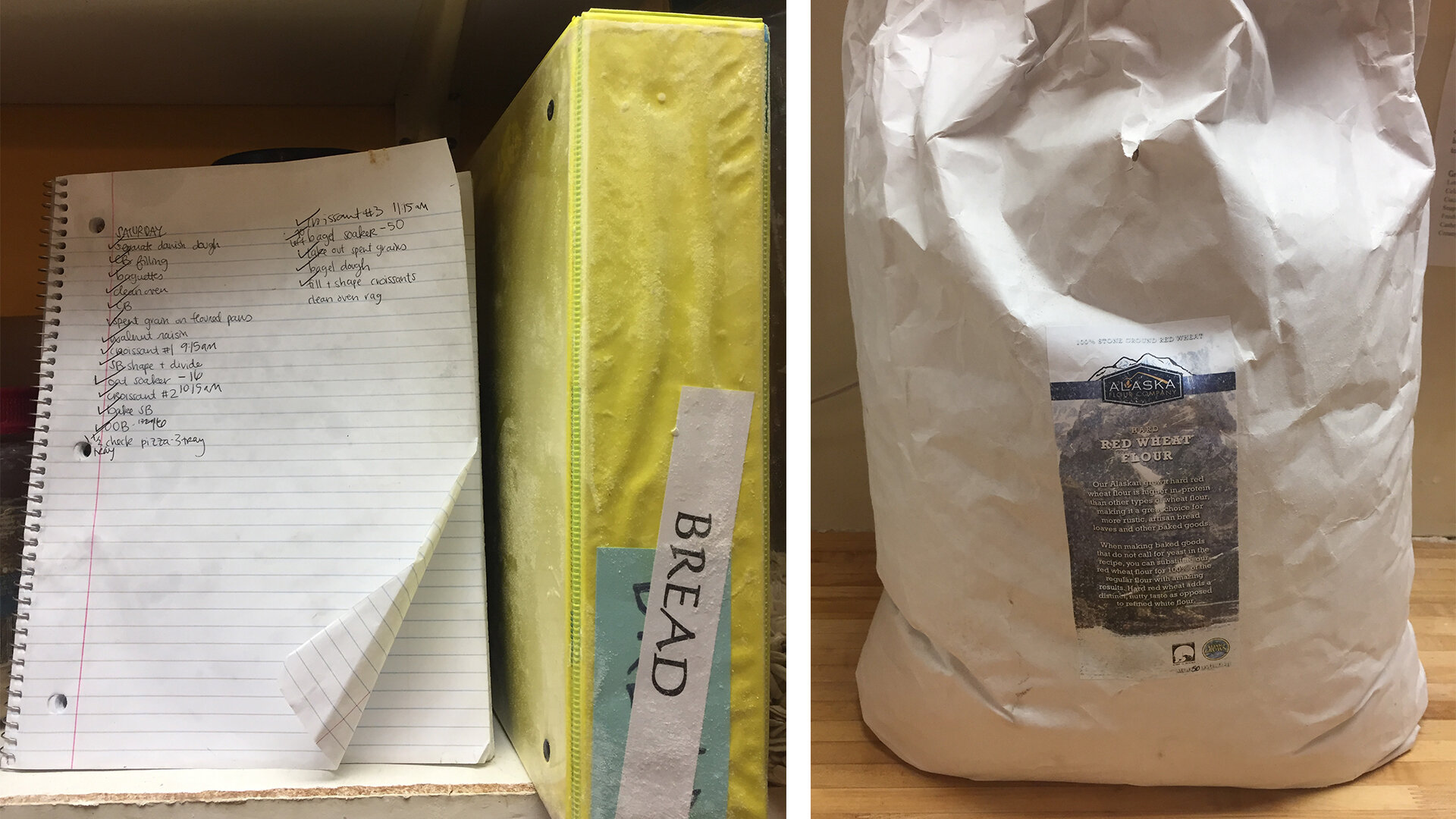

On the left: My ever-changing bread to-do list on one busy Saturday. On the right: Local, Alaska grown wheat.

But instead of feeling limiting, it’s all an exciting, creative, seasonal puzzle. And that’s something I’ve always liked about bread, even if I am tentatively aligned with the sourdough purists. You have to change all your timing on a hot day, amend your baking times for a smaller loaf, alter your kneading for a wetter dough, experiment with your flour type for a filled bread. And while I may not be throwing baking soda into my doughs anytime soon, I do feel more flexible, adaptable, and experimental with my breads now — and definitely even more excited to try some new bread hacks back in D.C.